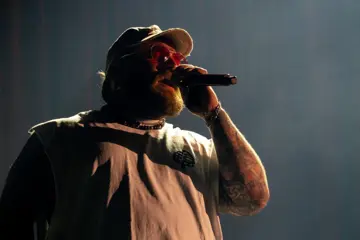

Sonic Youth

Sonic YouthFor just over 20 years, the Big Day Out was a rite of passage for many Aussie music lovers. The annual travelling music festival began life in 1992 as a one-off affair, bolstered by fortuitous timing and a burgeoning alternative music scene, but in no time at all, it became the foremost summer festival in the country.

By the time 2014 rolled around, its legacy was cemented, and many could have assumed an indefinite continuation of the event. However, the festival held its last edition in Perth on February 2nd, 2014, with no prior announcement or fanfare.

Though its future was left uncertain at the time, a ten-year gap between events seems to have cemented the fate of what was once the biggest travelling music festival in Australia. Thus, with a decade of lonely summers now in our rearview, it’s time to take a look back at the history, growth, and legacy of the Big Day Out festival.

Origins

To most, the history of the Big Day Out begins and ends with Nirvana. But before the Seattle grunge rockers helped to secure the success of what was to come, one needs to look at Sydney music promoter Ken West. At the time, West would have described himself as a "jack of all trades", trying his hand at almost every aspect of the touring process as he toured bands like the Ramones, The Birthday Party, Debbie Harry, Beasts of Bourbon, and more.

During the ‘80s, he entered into a chance partnership with the Melbourne-based Vivian Lees, who was at the time managing a little band called Hunters & Collectors. Pairing West’s art-focused mindset with Lees’ business knowledge, the pair soon became a successful team of promoters, and as the ‘90s rolled around, it wasn’t uncommon to see tour posters adorned with the Lees and West name.

In 1991, the pair were looking to bring frequent visitors Violent Femmes back to Australia for their largest tour to date. However, despite the draw that the Femmes had become by this point, Lees and West realised for a tour like this to be successful, and for the Femmes to play bigger venues, they needed a strong support act on the bill.

Fellow promotor Steve Pavlovic soon stepped up to the plate. Having toured Mudhoney in 1990, the influential grunge outfit recommended that Pavlovic should bring their friends Nirvana out to Australia. Given that Nirvana were themselves longtime fans of the Femmes, they were eager to make their debut trip to the country.

However, West had ideas bigger than just a standard tour. Inspired to build a larger event with multiple stages and a diverse lineup after seeing the Violent Femmes perform at the long-running Milwaukee festival Summerfest, West decided it was time to put his idea into action.

Making the Femmes’ Sydney gig a one-day festival initially called Kenfest, he moved the event to the Hordern Pavilion, added another stage, and began to curate a lineup that would make any self-respecting fan of Aussie alternative jealous: Beasts of Bourbon, Yothu Yindi, Clouds, You Am I, Cosmic Psychos, Falling Joys, The Meanies, and still more.

A daring venture to host such a stacked festival at the best of times, the burgeoning festival suffered from immensely slow ticket sales until the pieces fell into place.

With the festival slated to take place on January 25th, 1992, Nirvana would release both their landmark single Smells Like Teen Spirit and the iconic album Nevermind just four months earlier. Without even planning to, Lees and West had managed to nab the biggest band in the whole world for their event.

One person who remembers the vibe at the first Big Day Out well is Tony Mott. Already a well-respected photographer in his own right at the time, Mott had known West since meeting at the Sydney Trade Union Club in the ‘80s when West was doing the lights for Ed Kuepper.

Mott joined the Big Day Out in 1992 to document the event and soon became the official photographer of the event, snapping both live shots and portraits of artists. Some of the most famous images of the Big Day Out were likely taken by either Mott or fellow photographer Sophie Howarth.

“The vibe was phenomenal because of the timing of Nirvana,” Mott remembers. “Smells Like Teen Spirit came out and it just went through the proverbial roof. The reality is Nirvana probably could have done four entertainment centres at the time.”

Suddenly, the tides turned, the festival sold out, and the newly-renamed Big Day Out was one of the most anticipated events on the calendar. Just two weeks before the show, Nevermind topped the US charts, and as a result, Nirvana’s 7 pm slot at the Hordern Pavilion overshadowed most of the other bands on the bill – including Yothu Yindi and the Violent Femmes, who played directly after the Seattle groups.

“Nirvana was great, except the Hordern’s never before – or since – seen as many people,” recalls Mott, “and it was like a bloody sauna when they played.

“Despite popular belief, they weren't that great at the Big Day Out. They were pretty much going through the motions, and Kurt [Cobain] wasn't very well. The Selina's gig and Phoenician Club gig that they played that year were what Nirvana was all about.”

One of the many attendees at the 1992 Big Day Out was a 13-year-old Ben Lee. At the time, Lee had noted there was limited access for underage music fans like himself to see live music. With a desire to see punk shows and local indie bands, he admits that while being able to see acts like Nirvana and the Violent Femmes was exciting, it was the other end of the spectrum that really appealed.

“I was really excited about seeing the Hellmenn, The Hard Ons, Smudge, The Welcome Mat, Massappeal, and indie bands that very rarely played for kids,” he remembers. “That was just massive for me.

“Usually these shows were maybe one every few months, but the idea that I get to see all those bands on one day just felt huge.”

Though he didn’t foresee it holding the massive historic weight it would one day, the inaugural Big Day Out has often been associated with Lee’s decision to enter the world of music. Not long after, the groundwork had been laid for Lee to form Noise Addict.

Just over one year later, Noise Addict would support Big Day Out headliners Sonic Youth at a headline show in Sydney.

“I think what blew me away and made me want to start a band was seeing Nirvana, who were on their way to becoming the biggest band in the world at that moment,” Lee recalls. “But it was just clearly like it was three friends standing on stage. banging through their songs using the house light guy.

“It was really punk, and I think what inspired me was the mixture of how accessible it was, how big it was, and how exciting it was mixed with the simplicity,” he adds. “Because often when you go see a big show, and there's a super high production value, it feels really out of reach as a musician. You can't even imagine the steps it would take to get to be the one on that stage.

“Whereas when you saw a band like Nirvana play, from a technical aspect, the whole thing didn't seem like rocket science. It seemed like you and two other friends could get together, make some noise, and be standing at a packed Hordern Pavilion blowing people away.”

Growth

Though it was initially planned as a one-off affair, the positive reception to the Big Day Out’s debut emboldened Lees and West enough to give it another go.

This time, however, it was going to be bigger, better, and go further. Though they didn’t have the selling power of a band of Nirvana’s calibre on the bill, they did nab ‘Godfather of Punk’ Iggy Pop, alt-rock pioneers Sonic Youth, Mudhoney, Nick Cave & The Bad Seeds, and ‘repeat offenders’ like You Am I, Cosmic Psychos, and the Beasts of Bourbon.

Emblazoning the posters with the words “on the road”, the Big Day Out headed west, expanding its itinerary to include Melbourne, Adelaide, and Perth and allowing the festival to lean into West’s original vision for the festival.

“I wanted urban mayhem, I wanted controlled chaos, but I also wanted cold drinks, nice food, lots of choice, good drainage, lots of toilets and great production,” West would later recall. “Then I wanted people to learn about music, go as hard as they wanted and be able to get home safely at the end of the night.”

By 1994, things were continuing to expand. The festival added Gold Coast and Auckland to their tour dates, and with a lineup that included Soundgarden, the Ramones, Björk, and the Smashing Pumpkins, it was clear that the Big Day Out was unlike anything else, thanks in part to its diverse lineup which would draw in a combined 46,000 punters.

“I was on the Phil Collins tour, and I was with Paul Dainty – the promoter – in the fourth year, and I remember him saying, ‘What's this Big Day Out thing?’ I've never heard of any of these bands!” Mott remembers. “He couldn't comprehend how they were pulling 20,000 plus in each city with bands that just weren't on the charts.

“Smashing Pumpkins, the Ramones, Björk, Urge Overkill, all those bands in those early years, were about to go mainstream, but they weren't mainstream yet. Ken and Viv were very good at hearing music coming.”

Later, other festivals tried to mimic the approach of the Big Day Out, but they weren’t able to match the experience, the lineup, and the vibe that the festival provided. One famous example is the failed Alternative Nation, which despite featuring Nine Inch Nails, Tool, The Flaming Lips, Faith No More, and a young up-and-comer named Lou Reed, was deemed a “total failure”.

“Somewhere around the late ‘90s, the Big Day Out changed where established bands were headlining, like, putting the Soundgarden on as a headliner,” Mott remembers. “Sounds easy now, but at the time this band was not getting mainstream airplay.

“A lot of people in mainstream music were just gobsmacked that six years in, they were doing five cities and pulling 20-40,000 in each city,” he adds. “No one believed it, and then all of a sudden it happened, and then all the major promoters thought, ‘Oh, we want some of this,’ and they tried and failed.”

This massive growth also occurred behind the scenes, too. In 1994, the festival welcomed Sahara Herald to the team, and she would go on to become the National Event Coordinator for the event until 2011. Another addition was Peter Mackay, better known as Duckpond.

After working as the lighting designer at the first edition, he became the Ambience Director in 1993, resulting in the launch of the Lilypad Stage. Something of a cross between a source of respite, music, and chaos, the Lilypad Stage was one of the winning aspects of the Big Day Out. Alongside musical performances from wildcards such as Kamahl, it included art installations, zany antics, and – as many would remember – copious amounts of drugs and nudity.

“They've had Kylie Minogue topless, they've had Dave Grohl doing jazz, they've had Kamahl; loads of the bands go out to the Lilypad Stage and just loved it,” Mott remembers.

“The Lilypad Stage was also great for morale because they'd be in a hotel bar, they arranged a lot of the parties, and they were wacky guys,” he adds. “At one point Glastonbury wanted to buy the Lilypad Stage.”

By the midpoint of the ‘90s, the Big Day Out had already grown to be an opportunity for rising homegrown stars to rub shoulders with icons from around the world. 1995’s lineup would see Ministry, Primal Scream, Hole, The Cult, and The Offspring as headliners, but names like Silverchair, Tumbleweed, and The Mark Of Cain were probably bringing in just as many interested punters from the combined pool of 130,000.

The festival would also manage to be documented for posterity somewhat with the 1996 event. While Porno For Pyros would top the bill alongside names like The Prodigy, The Jesus Lizard, and Tricky, it also included Rage Against The Machine. Highlighting their intense stage show and the fervour they would inspire, footage of the band’s appearance at the Sydney Big Day Out would immortalise the festival for future generations.

One band who appeared on the 1997 lineup (which was headed up by repeat offenders Soundgarden, The Offspring, and The Prodigy) was Jebediah. The young Western Australia band only played the Perth leg in their first appearance, but they would become a staple of the festival in future years, touring on the 1999, 2000, 2003, and 2005 legs of the festival.

“My first Big Day Out was in 1995 as a punter, and then I went again in 1996, but very soon after that first one in 1995 was when Jebediah formed,” remembers frontman Kevin Mitchell. “For Vanessa [Thornton], Chris [Daymond], and myself, the Big Day Out was like the pinnacle of live music; it was the ultimate gig. It was the dream; the Disneyland of gigs.”

Jebediah would play the local band stage at the Perth Big Day Out, performing at the same time as world-renowned electronic act The Prodigy. For a young band though, they made the most of the experience.

“I remember me and Chris both stage-dived at the end of our set,” Mitchell remembers. “We jumped off the stage into the crowd, which was such a fun memory as well.

“It's hard for me to kind of really sort of do justice to what that festival meant for us and what it represented,” he adds. “It was such a sum-of-its-parts kind of thing and so much more than just a rock and roll gig.”

By the time they would release their debut album, Slightly Odway, in late 1997, they were primed for another appearance at the Big Day Out, but that wasn’t to be. Somewhat ironically, 2024 will also see Jebediah releasing their new album, Oiks, but like when they released their first record, there’s no Big Day Out on hand for them to play at.

Though the 1997 event was another success for the promoters with attendance figures of 210,000, it was slated to be the last for a while, with a new festival called Starbait set to appear in its place, and the last event fittingly subtitled ‘Six And Out’.

Unlike the Big Day Out, Starbait was to focus on the electronic side of things. The Prodigy were tapped to headline, with Black Grape, Regurgitator, Sonic Animation, Bexta, and more all planned to visit the usual cities. Sadly, poor ticket sales forced the cancellation of Starbait, and Lees and West soon began laying down the tracks for their return in 1999.

The Mid-Period

By the time the Big Day Out returned for its 1999 edition, it was facing some competition. Festivals like Homebake had begun touring the country (complete with a lineup of local acts who would easily fit on the Big Day Out), while events such as Livid, Falls Festival, and more were helping to prove the draw of alternative music. So how could a large-scale event cut through the noise?

The answer was by bringing in names unlike anything other festivals could secure. The 1999 festival was immense. Headlined by Hole, Marilyn Manson, and Rammstein (though the latter cancelled days before the kick-off), fans of rock were well-catered for as ever.

“It didn't really matter for us that there was no Big Day Out in 1998 in the end because they gave it to us in 1999, then they gave it to us again in 2000 and by then, we'd already put out our second album,” remembers Mitchell. “So we got to do it the whole thing two years in a row, which I think was a pretty rare thing back then.

“It was like being embraced into this family that, for years, had sort of been on the outside of, just looking in,” he adds. “Embraced into that world and in that family was amazing and it was part of our coming of age experience. I guess that's why I've got so much reverence towards it when I think about it because obviously it was really important in terms of our career.”

However, bolstered by the cancelled Starbait festival, organisers had attempted to bring a greater focus on electronic music into the event, with acts like Underworld, Fatboy Slim, and Roni Size helping to expand the clientele that would visit the festival.

“I certainly didn't ever see the Big Day Out being as successful as it was, and I don't think Ken and Viv did either,” Mott remembers. “They got it right, but I remember those early years; they were getting money from mortgaging their houses in those first five or six years, so it could have gone arse over tit very easily.

“There was more than one time I’d sat on flights to Auckland with Ken and Viv where they'd talked about the ticket sales being really bad in Adelaide. They were worried all the time, and it wasn't a foregone conclusion.

“But there was a period eventually where it became established,” he continues. “I always think the year 2000 was possibly the turning point where it became massive. It sold out, but the headliner was the Red Hot Chili Peppers and everybody in the country knew who they were.”

“The Sydney Big Day Out in 2000 is probably the biggest crowd that we've ever played to in our lives,” remembers Mitchell. “I feel like that was when it felt like we had reached some kind of commercial peak because we were playing on the main stage, playing a good spot in the afternoon, and the crowd was just ginormous. That was when the band had really broken through to a much bigger audience at that point in time.

“Being on the Big Day Out, it really helped you grow an audience, but it also helped you realise where you’ve gotten to as an artist” he adds. “All of a sudden you've got tens of thousands of people in front of you.”

It was also around this time that the festival started to become less of an underground affair and much more of a mainstream event. In its early years, the festival was popular amongst those within the alternative culture, but by the turn of the millennium, its profile had risen to a point where it was a far more established event, and the secret had gotten out.

“I remember when I first started seeing in mainstream news media, like in The Age or The Herald or whatever, there'd be a little article about who won triple j’s Hottest 100,” Mitchell remembers. “I had always just felt it was just this thing that existed in triple j land and no one else really cared.

“I always kind of thought of the Big Day Out like that as well. I always thought it was this event all those people from all the different cross sections of musical tastes and interests or whatever. It was that one point of the year when that whole community was all at the same gig at the same time.

“That's what it was to me, and that's what it was in my head,” he adds. “But you could see that slowly start to change over time.”

Much like when larger promoters tried getting in on the action with their own rival events in the ‘90s, the Big Day Out had managed to become the peak of alternative culture within Australia and began to attract outsiders. The festival became bigger and more popular, and as a result, the artists showcased on the lineups benefited from increased exposure, new fans, and the chance to rub shoulders with their own idols.

“It went from sort of being a genuinely niche, alternative thing to becoming a more of a mainstream event,” Mitchell notes. “Which is inevitable; that's what's going to happen if you build something that's really cool; obviously, everybody's going to want a piece of it.

“But it kind of just felt like we were getting to live our dreams a little bit.”

“It was great watching things like Joe Strummer playing in 2000, and the Red Hot Chili Peppers just couldn't believe they were headlining above their idol,” Mott remembers. “They wanted their playing times changed so they could check out Joe Strummer on the side stage.”

Indeed, at the start of the millennium, the Big Day Out was looking ahead with positivity. As the Financial Review reported at the time, Lees and West brought in “gross income of $4.3 million in 1999 and $7.5 million [in 2000]”.

In fact, the festival was looking to expand beyond its local confines. While an English festival of the same name had been launched by MCP Promotions' Tim Parsons and a former colleague of Lees and West, John Jackson in 1999, Lees and West were reportedly hoping to expand this event. Likewise, 2001 would potentially add a second Sydney date and take the festival over to Cape Town in South Africa following the Perth show.

While the 2001 festival would indeed be a memorable one, it would instead be for all the wrong reasons.

Its lineup included names like Rammstein, Placebo, PJ Harvey, and one of the most infamous bands in music at the time; Limp Bizkit. Ahead of the festival’s announcement in 2000, organisers had struck a handshake deal with Pearl Jam to appear as headliners. Sadly, this fell through when nine concertgoers were crushed to death during the band’s appearance at Denmark's Roskilde Festival, causing the band to not only almost split but also to vow to never play another festival.

As a result, organisers were left to scramble to lock in another band who were of headline quality and would fit in with their budget. Despite not being deemed a good fit for the festival, they managed to secure Limp Bizkit.

At the time, the Florida outfit were the subject of widespread controversy for their onstage behaviour, lyrical content, and the likes of their Woodstock 1999 performance, in which audience members took songs like Break Stuff literally, and engaged in widespread violent behaviour.

Though the Auckland and Gold Coast legs of the festival took place as expected, the Sydney event was marred by controversy early on when At The Drive-In frontman Cedric Bixler-Zavala would call out fans who were engaging in unsafe behaviour in the crowd.

“I think it's a very, very sad day when the only way you can express yourself is through slam-dancing,” he would tell the crowd before eventually calling the audience sheep, bleating at them, and walking offstage.

Only 90 minutes later, Limp Bizkit would begin their headline performance. Almost immediately, intense crowd behaviour saw security attempt to remove fans from the mosh pit, while frontman Fred Durst was heard to criticise security efforts and grow frustrated by the delay. Sadly, the crowd surge would crush 16-year-old Jessica Michalik, resulting in her passing five days later.

Limp Bizkit swiftly and unceremoniously left the festival following the incident. Legal action ensued, with Durst blaming organisers for a lack of security. While a coroner’s inquest would absolve the band of wrongdoing, Durst was blamed for “inflammatory and indeed insulting” behaviour towards security staff at the time of the incident.

Ultimately, it felt to organisers as though the festival had “lost its innocence”.

"It most certainly did make us all re-evaluate what we were doing, on every level, and I am not just meaning professionally either," Sahara Herald told Double J in 2019.

"We'd all been working our asses off to deliver a show that was meant to bring joy. And it didn't."

The Big Day Out was resolute, however, and with the support of Michalik’s parents and after introducing the D-barrier (which would feature at all future festivals), it managed to survive any criticisms of safety that were levelled against the event.

In 2004, it experienced some of its biggest events thanks to a lineup that included heavy metal icons Metallica. High demand would result in the inclusion of a second Sydney date, which would later sell out.

The calibre of headliners in this era would result in swift and frequent sold-out affairs thanks to the likes of the Beastie Boys and System of A Down (2005), The White Stripes and Iggy And The Stooges (2006), Tool and Muse (2007), Rage Against the Machine and Björk (2008), and Neil Young (2009).

“The reality was, the Big Day Out was bigger than the bands,” Mott notes. “Every kid wanted to go to the Big Day Out, then they'd see the bands on it, and of course, there was so much variety with 30-odd bands in a day, it was phenomenal.”

Final Years

Despite their massive events, it was in 2011 that the Big Day Out’s eventual end could have perhaps been predicted by longtime attendees or cynical observers.

Attendance figures had hit 337,000 for the 2010 edition, but in November of that year, trouble seemed to be brewing when Lees and West announced they had ended their partnership. “I am a passionate supporter of the Big Day Out and the musical legacy I have created with Ken West who will now continue to produce the show as sole producer,” Lees told media outlets.

West also expanded upon their creative partnership, which usually saw him as the more exuberant, outgoing one, while Lees was the quieter, more reserved half of the equation.

“Tensions were always constant. It was my vision for the show, and his concept was to streamline it as much as possible so he could understand it,” he said. “You could say we stayed together for the children — the children the Big Day Out and everyone associated with it!”

Just two months later, and weeks before their 2012 event, it was announced that the Big Day Out had formed a partnership with Texas-based promoters C3 Presents following the sale of Lees’ stake in the annual event.

With C3 Presents being in charge of other events such as the iconic Lollapalooza, they noted they were intent on taking the festival "forward together as business and creative partners” but claimed it was “too early to tell” about international expansion of the festival.

Despite internal tensions, the 20th edition of the Big Day Out would go ahead in January of 2012, with Soundgarden and Kanye West as headliners, though the latter would – ironically – only perform at East Coast legs.

Plans for the 20th anniversary edition had been entirely different to what would eventuate, however. Prior to the kick-off, West would reveal that both Prince and Blink-182 had requested to perform at the festival, while US rapper Eminem proved too expensive to procure.

As Mott recalls, big names like Prince weren’t ever far from the festival’s mind, though Lees and West would always try and deliver unexpected fare onto the lineup. While Henry Rollins performed with The Hard Ons in the first year, a pre-controversy Gary Glitter had also been floated as another potential collaboration for the Sydney rockers. One idea that never got past the back-office discussions stage was getting AC/DC to play an unannounced set.

“Malcolm Young's kids used to go to the Big Day Out and loved it, and they were the ones persuading their dad, ‘Man, you gotta play this festival!’” Mott remembers. “Their fee is so huge, the Big Day Out can't afford AC/DC, so it's never going to happen.

“So the idea was, if they were warming up for an international tour, they would do a gig in the afternoon, just a warm-up. But I must emphasise, this was just people talking in an office, but this is where the sort of ideas were coming from.”

The struggles in delivering an event large enough to honour its 20th anniversary proved difficult, and the ultimate reaction to the lineup was divisive, to say the least. Ultimately, the widespread negative reaction to the lineup (and subsequent low ticket sales) was what reportedly resulted in Lees’ departure.

"When we went through the process, I said 'It has to go forward,'” West said in 2012. "My business partner decided after it went on sale – he looked at all the figures and decided that he didn't want to do it ever again. It was over.”

The 2012 edition would also be the last to visit Auckland due to a lack of financial viability, though its 2013 event would be deemed a “comeback of sorts” thanks to a lineup that featured names like the Red Hot Chili Peppers, The Killers, and the Yeah Yeah Yeahs.

In late 2013, however, the Big Day Out’s organisational team would expand to include AJ Maddah, who had risen to fame as the promoter behind touring heavy metal festival Soundwave.

The move came after speculation that West was himself going to exit the festival, though Maddah would confirm he held an "equal" financial interest in the Big Day Out and that West did intend to "wind back" his role.

“The percentage of Aussie bands at the Big Day Out will not change,” Maddah said at the time. “There will be no change to the spirit of the Big Day Out. It’s Ken’s vision, and I’m working for him.

“For 20 years it’s been my ambition to work for the Big Day Out. It’s been a great festival for 22 years. I don’t need to fuck with that.”

However, issues were still incoming. The 2014 lineup would feature Pearl Jam, Arcade Fire, and Blur, though the latter would pull out just two months before the event was to begin. Even with the festival’s own white whale procured for the bill, it didn’t resolve all the problems that were on the way.

“The entire career of Big Day Out, they were trying to get Pearl Jam,” Mott remembers. “They had them once and then the kids died at Roskilde, and Pearl Jam cancelled. They didn't want to do festivals anymore, so they lost them. They nearly got 'em again.

“Right at the end, they got them for that last one, and – this is going to sound rude to Pearl Jam – but they'd become irrelevant. The Pearl Jam fans had grown up and didn't want to go out to a concrete jungle out at Homebush. They didn't pull a crowd of kids; there was a new generation.”

Low ticket sales had already resulted in the cancellation of a second Sydney show for 2014, and Maddah would later confirm the festival would not return to Perth due to ongoing financial concerns and the “financial catastrophe” the event would end up being.

Despite all the issues that circled around behind the scenes, the 2014 event would go ahead as planned, and at 10:45 pm on Sunday, February 2nd at Arena Joondalup in Perth, the last notes of Major Lazer’s set rang out around the venue, with punters unaware these would be the final moments of the Big Day Out brand.

Immediately after the 2014 event, there were no indications to average punters that the future of the festival was in any imminent danger. That is, despite reports of the festival losing “between $8 million and $15 million”, rumours that organisers have “inflated attendance figures”, and a potential court case between Maddah and C3 Presents on the horizon.

In June of that year, documents were obtained that confirmed that not only had Maddah stepped down from his role as Director and transferred his stake to C3 Presents, but that West had previously transferred the remainder of his stake to Maddah in November 2013.

As a result, the festival found itself entirely owned by the US company. One day later, C3 Presents confirmed the cancellation of the Big Day Out for 2015, adding that they “intend to bring back the festival in future years”, something which Maddah would echo.

Lees responded to the cancellation of the festival by noting it was unlikely that an event with the legacy of the Big Day Out would ever be matched or replaced by anything else.

“The Big Day Out has been, and will always be, the festival in Australia,” he said, “and if people are expecting something better to come along tomorrow, then they shouldn’t be holding their breath because it’s not going to happen.

“Big Day Out set the high benchmark which is not going to be succeeded by a one-day festival in the near future for sure.”

The Legacy

For many Australians of a certain age, the Big Day Out is inextricably linked with fond memories of music. Whether it’s the feeling of musical discovery, camaraderie, or just youthful nostalgia, it’s difficult to find any former attendee who doesn’t look back upon the festival with a sense of regret in regard to its absence from the live music scene.

Over the years, there have been countless reflections on the festival and what it means to people. Until recently, it was almost impossible to find any burgeoning artist who hadn’t been impacted by other artists they had witnessed at the Big Day Out.

However, it’s difficult to effectively capture the broad spectrum of experiences the festival caused. As such, it’s better to step back and view it as a whole to illustrate just what Lees and West managed to achieve over the years from its humble beginnings.

In 2019, Double J took a look back with their five-part podcast, Inside The Big Day Out, which focused on its spectacular rise and eventual fall.

In January 2022, Ken West marked the 30th anniversary of the festival by launching a website called Ken Fest, in which he shared a number of chapters from a book he had written.

Given the working title of Controlled Kaos, the chapters focused heavily on the early years and the rising success of the event.

"The Big Day Out for me was life-changing, and the first six years were the heart and soul of a great adventure,” West said. “A different world, innocent, dangerous, optimistic and a lot of fun.”

Three months later, in April 2022, West would pass away at the age of 64. Though he confirmed the entirety of his book had been written, a release date has still not been announced as of February 2024.

The question now becomes: what of the future of the Big Day Out? With West now sadly gone, Lees no longer being involved, and C3 Presents still owning the rights to the festival, it’s unclear when or if the festival could ever return.

Towards the end of its life, the Big Day Out struggled with a few years of difficult lineups, diminishing ticket sales, changing tastes, and rising costs. Though it persevered, these struggles would take a toll, especially in a climate that featured an oversaturation of music festivals and events and constant bidding wars for artists.

It’s easy to say that the musical landscape in which the Big Day Out first flourished is far removed from the one in which its demise occurred, but it does inspire one to ask if a festival of its kind could still exist today.

Indeed, while events such as Groovin The Moo, Good Things, and Falls Festival, to name a few, still continue the touring format that Big Day Out was heavily associated with, these festivals have also been forced to contend with similar issues.

After a decade away, would it be enough for nostalgia and name recognition to sell tickets for any potential revival of the Big Day Out? Undoubtedly, older attendees would claim that any lineup that would actually sell tickets is not representative of the classic era of the Big Day Out, and it’s difficult to say whether an event that would appeal to older attendees, younger attendees, and those who never attended would be financially viable.

Part of what made the Big Day Out so special, however, was the sense of community it inspired, the friendship between artists, and for some, it was a testament to the Aussie spirit of creating something special, seeing it grow out of hand and adopted by the public.

“The standout moments were The Prodigy converting from the dance stage onto the main stage and it working, and the Black Eyed Peas doing the same thing,” remembers Tony Mott. “God, there's so many highlights; Iggy Pop, the Beasts of Bourbon, and Sonic Youth, jamming I Wanna Be Your Dog on that second Big Day Out.

And of course Nirvana; not so much their playing, but just the whole thing that this was the changing of music,” he adds. “Grunge had arrived, and mainstream music was getting hammered by indie music. That was just the vibe of that first Big Day Out, and that's why the big day out was successful; because they came in at that time.”

In early 2023, much of Australia found themselves reminiscing on the ‘right time, right place’ feeling that accompanied the very first Big Day Out with Nirvana.

Fellow touring event Laneway Festival had managed to nab UK electronic genius Fred again.. for their next event. At the time, he was riding high off the popularity he had gained throughout lockdowns and stellar performances such as his Boiler Room appearance (a different Boiler Room to the Big Day Out stage of the same name), and by the time he touched down in Australia, he was one of the biggest names in music.

His inclusion on the Laneway lineup reminded many of Nirvana’s appearance at the Big Day Out, with his sideshows selling out immediately, pop-up shows packed to dangerous levels, and his festival shows being some of the biggest on record.

This is the sort of magic that managed to earmark the Big Day Out. It wasn’t just the fortuitous timing that became associated with its debut; it was the sense of feeling like you were watching something incredibly special at every event. Most of the time, you were, and it gave nearly every punter the sense that they, too, were just lucky enough to be witnessing something at the right time in the right place.

Most importantly, much of the impact of the original Big Day Out was because of the team behind it, the risks they took, the ground they broke, and the impact they made upon the global music scene.

“In a lot of ways, they kind of designed the template of how festivals worked as they went along,” notes Kevin Mitchell. “These days, a couple of cowboys can't just come along and just something like that now because there are just so many rules, regulations and all that stuff that now you've got to deal with as well.

“The big thing was that they were pioneers because a lot of that map hadn't been drawn yet, and they were kind of helping to create it themselves.”

Could the Big Day Out ever return? Well, like 2000 performer Joe Strummer once said, “the future is unwritten”. But what we do have is a 22-year legacy of a festival that held 121 events and entertained more than 5,000,000, and – in the absence of a mind like Ken West – will likely never happen again.

As of 2024, C3 Presents have made no plans in regards to any potential future return of the Big Day Out.

Ken West’s Controlled Kaos book is still unreleased, with no word as yet of a potential release date.

Frequent performers Jebediah will also release Oiks, their first new album since 2011, on April 12th, with new single ‘Motivation’ arriving on February 14th.