Dirty Three

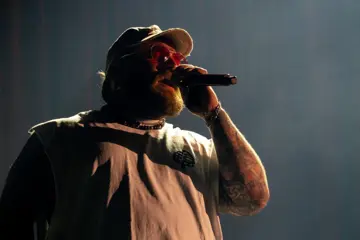

Dirty Three“Am I Greek? Fuck, I wish I was…sweetheart. Can I call you sweetheart?” Warren Ellis said early on in the intermission between songs. Such was the decompression needed in the comedown from the heady, wistful, life-destroying and equally life-affirming trance of Dirty Three’s instrumental melange.

Back on Enmore Theatre’s stage after some time: “Five…fuck, more than five years… remember COVID? It’s been some time.” And indeed, it has.

Off the back of the Melbourne/Naarm-based trio’s first release in over a decade - Love Changes Everything I and II - Ellis on keys and electrified (electrifying) violin returns with the “Ayatollah of rock and roll-ah”, Mick Turner on electric guitar and the indefatigable, avant-garde, mercurial (or whatever Ellis said, mimicking James Brown’s original hype man, Danny Ray) drummer Jim White.

This is the sort of show you can believe the hype over. Tinged with nostalgic and nascent tales - part embellished meandering fact and part absurd hilariously crafted fiction - Ellis performed as decrepit/intrepid sex god jester with his lengthy and yet energising monologues as a way to bring some levity to this profound sonic experience.

But the music. Ah, the music! That’s what we’re here for. It is overwhelming, nuanced and pensive at times, transportative and transcendent at others.

Indian Love Song, for instance, opened with the primal picking of the reclining Ellis, blending with the drive of Turner’s guitar, which hung under the increasingly exuberant flourishes of the violin and the dilation of White’s drums, which expanded like the pupils of one bursting through the doors of perception.

Next, Ellis’ shrieking strings rang out as he rose - almost an apotheosis - from reclining to the upright Jack jumping over the candlestick, one leg bent upwards as he energised White’s percussive turns.

All the while, White’s and Turner’s eyes fixed upon their frontman, who careened this way and that way in a frenzy, where he only came up for air when it was over. Here the ascetic, here the Baudelairean surfeit - here a “fucking rock and roll band”.

“Fuck, it’s Tony Mott,” Ellis said in the breaths between songs. “Tony was one of those guys where you thought you were ‘rock and roll’, and you showed up, and Tony was there, and you realised you’d never be as ‘rock and roll’ as Tony.”

The distinguished music photographer would no doubt be chuffed for the shoutout. Yet, such was Ellis's shapeshifting talent to take us from the sublime to the ridiculous, from universal heights to primordial filth: “Christian, where’s my spit bucket?! Trust me, you don’t want me spitting on stage.”

The band’s chief roadie rushed out with the vigilance of a ball boy, supplying Ellis with a towel around his neck - “Got a white towel, Christian? Black’s a bit [morose].” - a bottle of water and his coveted spspittoonHe hocked a loogie visible from the bleachers. “I’ve got loooong COVID…”

“Sydney…We came to Sydney in the early nineties. Was anyone there then? Anyone remember? I think I do. We played a funeral parlour, and there was some kind of problem…In those days, I played a mop bucket, and the security chased me up the stairs and said, ‘You will never work this town again!’ I’d never been to Sydney and we were driving up in a ‘63 automobile and the gear stick came out…Everything I associate with Sydney is a box of longnecks and a bag of speed.”

His rambunctious yarns drew you in, feeling 2000 people feel like they were sitting across the pub from him. Pure class. And then, of course, the music.

Sea Above, Sky Below from 1998’s Ocean Songs - dedicated to Steve Albini, who produced the album in Chicago and gave Ellis words to live by: “Make sure you do what you came in here to do.” - yielding up a melancholic and tender instrumental meditation on - as Ellis described it - “falling into a hole...”

“...And you go outside, and even the birds are telling you to fuck off. All you’ve been eating for the last three weeks is peanut butter, and you can’t buy anything but peanut butter because it’s the only thing that comes out in the same form it goes in.”

Giant antique stage lights beam down with their warm, steady light as Ellis moans into the f-hole on his violin to simulate that usual moan and wail of his strings in the studio version. Little bulbs flash and flicker about the stage like fireflies before the Enmore stage lights explode into white pulsating wonder. In the despairing depths of the song, some inkling of hope emerges that Ellis describes as “you climb[ing] out of the hole and see three little angels - cherubs - named Warren, Mick and Jim.”

I could go on…Really, I could talk about how Ellis compared his habits to Elvis: “You know the cocktail they had Elvis on. That was lightweight.”

I could mention his successful canvassing of the audience for a belt. Or his rendezvous with the Godfather of Soul at an airport.

Or his resistance to the advances of ‘Sweetheart’ asking him to come home with him: “What? Come back to your place? It’s not a good idea. They only let me out for rock concerts. Then they put me in a room and wind me up.”

Or his bizarre analogies about Thai heroin in the mail.

Or even his realisation - upon the millionth listen to Billy Joel’s You May Be Right, and the millionth time he says “crazy” - that this guy’s never been truly crazy.

Or the meandering and stupefying fantastical journey to slay the Piano Man himself at his Boston hotdog stand.

But these words cannot contain the experience.