14 Music Industry Problems That Should Get More Press

Chris Dalla Riva lifts the lid on 14 annoyances, scams and loopholes that are holding our industry back.

Industry Opinion (The Music)

US-based Chris Dalla Riva is a musician who spends his days working at Audiomack, a popular music streaming service. He writes a weekly newsletter about popular music and data called Can't Get Much Higher. His writing and research has also been featured by The Economist, NPR, and Business Insider.

It feels like 99% of music industry press is focused on one of two issues: streaming royalties and the Ticketmaster antitrust case. Of course, these are major issues affecting an untold number of artists. But given that I spend an ungodly amount of time working in, thinking about, and making music, I often come across other pesky problems that get little to no press. This week, I want to give 14 of these issues their due.

#1 Songwriters Aren’t Paid for Their Labor

Let’s say you’re an artist working on a new song. You bring in a songwriter to help you finish it. Then you hire a producer to bring it to life. How are these people getting paid? For the producer, you will pay them upfront, along with giving them a small share of your royalties to share in the spoils if the recording becomes a hit. Songwriters aren’t so lucky.

The current standard is that songwriters don’t get paid upfront. Their only payment would be from the various royalties generated from their share in the songwriting. If the song flops, they don’t make anything. That isn’t fair. Songwriters deserve to be paid upfront for their labor and not just based on the success of their compositions, especially since those compositions can get shelved for years or never get released.

Furthermore, even if you’ve written a smash hit, the money isn’t going to get to you quickly. While most streaming services report recorded music royalties to labels every month, songwriting royalties are usually reported to performance rights organizations each quarter. This less frequent reporting leads to fewer and slower payments.

#2 It Takes Too Long to Enter a Concert

I’ve spent more time waiting to get into concerts in the last year than I think I spent waiting to get into every concert I’ve attended in the last decade. And this has nothing to do with the number of shows that I’m attending. It has to do with the infrastructure we’ve built around digital tickets.

Digital tickets are often very convenient, but I think they’ve slowed concert entry. Sometimes people don’t have the ticketing app opened. Sometimes they can’t get the tickets to scan. Sometimes all the tickets are on a single phone and the person has to have a venue employee flick through them one-by-one. It’s madness. Since I’ve never worked in live entertainment, I have no sense of how hard these issues are to fix. Nevertheless, it strikes me that two things might speed things up.

Rather than scanning a barcode, you should be able to enter by tapping in the same way that you can tap a digital credit card to pay for something

If you have multiple tickets on your phone, one tap should get everybody in at once

#3 Many Streaming Services Pay Artists Nothing

It’s easy to find press about how Spotify doesn’t pay enough in royalties. It’s harder to find press about how there are popular streaming services generating hundreds of millions in yearly revenue and paying nothing to artists, songwriters, or labels.

Apple App Store music rankings as of June 11, 2024

Don't miss a beat with our FREE daily newsletter

Above you will see the most popular music apps on the Apple App Store in the United States as of Tuesday, June 11. Not all of these are streaming services, but the ones that are should mostly be familiar: Spotify, YouTube, SoundCloud, etc. One probably isn’t, though: Musi.

Musi is a free streaming app that, according to a recent report from WIRED, has been “downloaded more than 66 million times since launching more than a decade ago.” As far as anyone can tell, it’s never paid anything out to anyone in the music industry despite generating more than $100 million in ad revenue in the last two years alone.

#4 It’s Very Confusing for an Independent Artist to Get Paid in Full

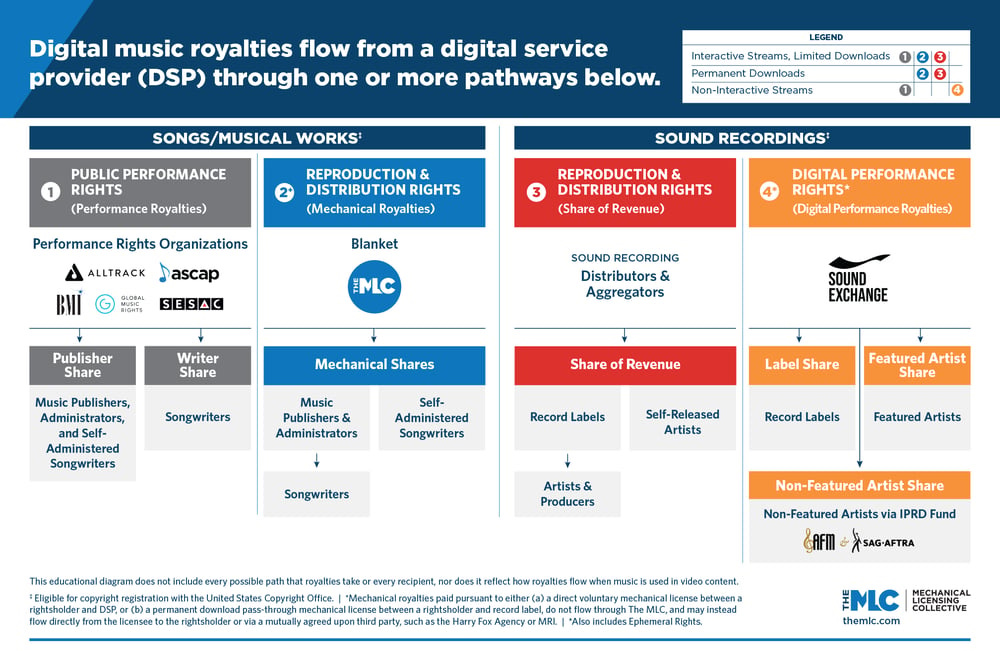

For every record, there are two underlying copyrights, namely the composition’s copyright and the recording’s copyright. When you play a song on a streaming service, both the owners of the composition and recording must be paid. That makes sense. But when you look at how those payments flow, you brain will quickly get tied in a knot.

Let’s start by focusing on the composition. When you stream a song, the songwriters must be paid out for the public performance of their work and the mechanical reproduction of their work. Again, this makes sense. But those two songwriting royalties are administered by two different groups. Performance rights organizations in the US (e.g. BMI, ASCAP, SESAC - their APRA equivalents) collect and distribute royalties for the public performance of songs. The Mechanical Licensing Collective, a recently established government body, collects and distributes royalties for the mechanical reproduction of songs (in Australia this is AMCOS).

Now, let’s turn to the recording. When you stream a song, the owners of the actual recording must be paid out too. If you are using an interactive streaming service, meaning a service like Spotify where you can directly choose what you are listening to, then those royalties are paid out directly to distributors or labels by the streaming service. If you are listening on a non-interactive streaming service, like Pandora or SiriusXM, then those royalties are collected and distributed by SoundExchange, a non-profit established by Congress in 2003 (in Australia we have PPCA).

In short, if you want to collect all of the royalties you are owed when people listen to your music online, you likely need to be signed up with four organizations, a distributor, a PRO, the MLC, and SoundExchange. While you must have a distributor to get your music on a streaming service, the latter three aren’t necessary. If you never sign-up, you will not get those other royalties. In fact, those organizations will generally only hold your royalties for three years. After that, they distribute them to all of the other artists in their system.

In an ideal world, there would either be more education about getting independent artists signed up for these services or a more efficient way to administer these royalties. The only royalty we are really good at getting to artists currently is interactive recorded music royalties. Those are the ones people spend the most time yelling about online because they are the only ones most people ever see. In all likelihood, the others should be paid out in a similar way for independent artists rather than having them sign-up with multiple organizations.

#5 AM/FM Radio Doesn’t Pay to Use Recordings In The US

In the US, if you turn on SiriusXM and hear “Downtown” by Petula Clark, Sirius has to pay royalties to the respective owners of the song and recorded music copyrights. If you turned to your local oldies station on AM/FM radio and heard the same song, they won’t be doing the same thing. Terrestrial radio only has to pay royalties on the song, not the recording. There is no good reason for this. SoundExchange has been lobbying for a long time for terrestrial and digital radio to be treated the same.

In Australia, we have our own radio woes, with PPCA currently fighting for the lifting of the 1% royalty cap.

#6 Spotify “Podcasts” are Filled with Illegally Uploaded Music

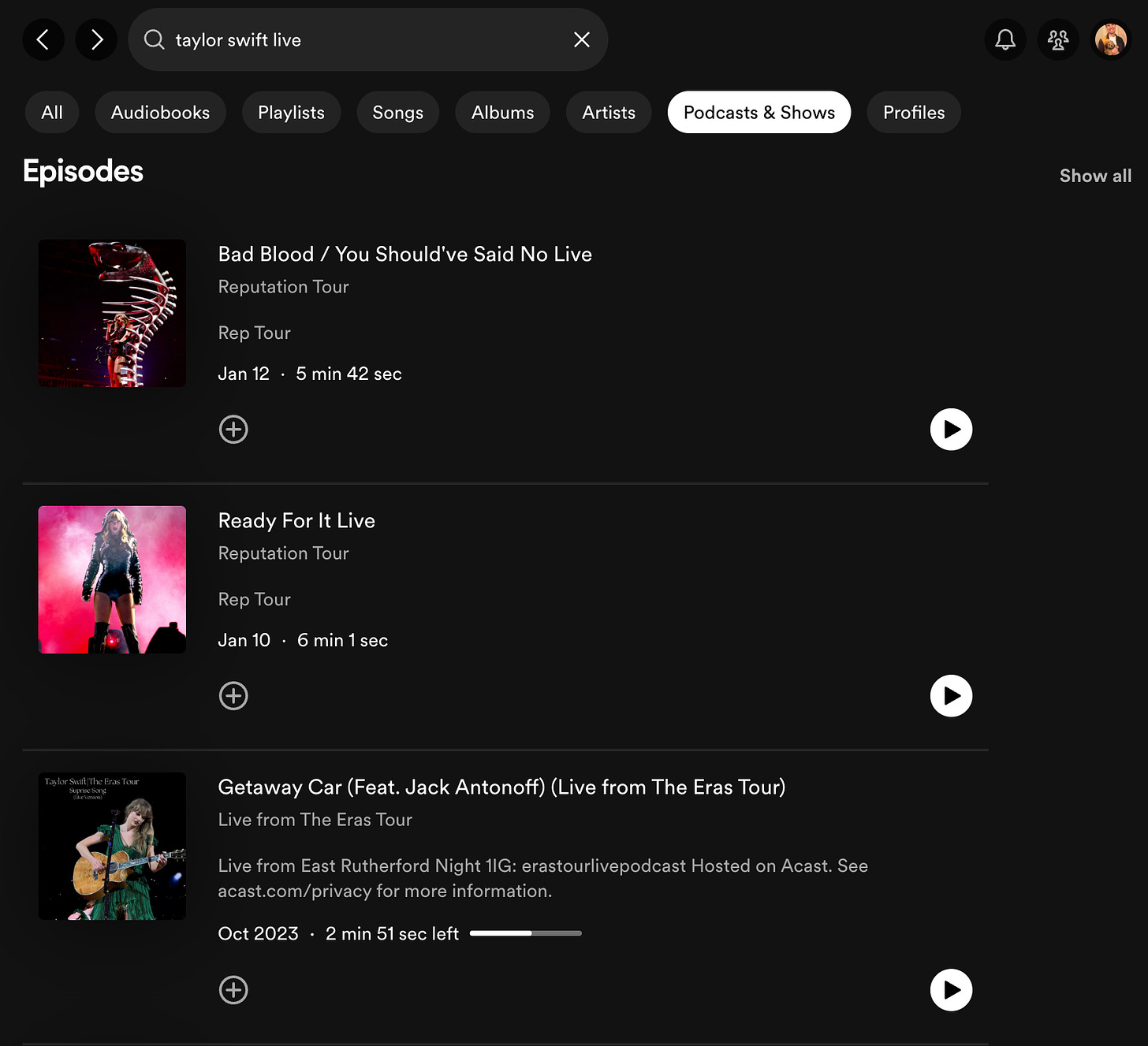

Music streaming services go to extreme lengths to make sure people aren’t uploading music that they don’t own the copyrights to. Mostly. In 2020, Variety reported that people were uploading music illegally to Spotify by marking that music as a podcast. Podcasts, enterprising listeners have discovered, are monitored less actively. In fact, if you search for popular artists and click on the “Podcasts & Shows” tab within Spotify, you will often find unsanctioned live recordings and remixes. No royalties are being paid for the usage of that music.

Live Taylor Swift bootlegs uploaded to Spotify as “Podcasts”

#7 Apple and Google Use Their Monopoly Power to Deprive Artists of Millions in Royalties

I’ve written at length about how recorded music royalties are paid out by streaming services. As a very brief refresher, the streaming service makes a bunch of money, takes their cut, and then divvies the rest up to artists based on how much their music was played. The problem is that the initial pool of money that the streaming service makes is much smaller because of monopoly power exercised by Apple and Google.

In short, when you purchase something in any app that you downloaded on the Apple App Store or Google Play Store, those tech behemoths are taking 30% of your purchase. Don’t get me wrong, those companies are owed something. It’s a tremendous amount of work to maintain these stores and process payments. But 30% is artificially high.

Compare Apple and Google’s transaction cut to what online payment processors take. Stripe, maybe the most popular payment processor around today, charges 2.9% + 30¢. In other words, if you purchased a $10 streaming subscription within a mobile app, the streaming service would only take home $7. If you did it via Stripe, the streaming service would take home $9.41. That leaves a lot more money for artists. For this reason, many companies won’t let you buy things within their apps because Apple and Google won’t let you use other payment options.

Some of this might be changing, though. Earlier this year, the European Union said that Apple could no longer force apps to use their payment processing within apps distributed on their App Store. This would bring competition into the payment ecosystem, thus bringing down fees and sending more money to artists. Apple, of course, will fight this to the ends of the Earth.

#8 Songs and Recordings are Becoming Equivalent in the Minds of Listeners

Something I talk about often is how in the last hundred years the music industry shifted from focusing on songs to focusing on recordings. Here’s a good example. In 1946, three different versions of the song “To Each His Own” topped Billboard’s National Best Selling Retail Records chart. Today, you’d be hard pressed to find pop stars releasing different versions of the same song at the same time. This shift is driven by the fact that recorded music is now so accessible that we equate a recording of a song with a song itself.

This poses an issue in the live music space. Often when you see younger artists perform, at least part of their performance will be recreated with a backing track rather than by musicians on stage. Some of this is driven by cost. Touring has just gotten so expensive. But another part of it is driven by the fact that audiences expect a performer to sound exactly like they do on the record. This expectation is silly. The stage is a completely different environment than the studio. Because of that, things that work well in the studio don’t necessarily work on stage. Our live music environment is diminished when we won’t let our artists reimagine their works.

#9 We Focus Too Much on the Supply of Music Rather than the Demand for Music

Everyday there are hundreds of thousands of songs uploaded to the music streaming services of the world. That means that there is more music released in a matter of weeks than was released across decades of the 20th century. In other words, making and distributing professional quality recordings has never been easier. Because of that, tons of companies — from BandLab to Suno to Landr — have cropped up over the last decade to try to build, maintain, and monetize an infrastructure that supports an ever-growing supply of artists and songs. The problem? We aren’t investing as heavily in inducing demand for those artists and songs. Here’s what Eric Pan recently wrote to me about this:

Next to zero effort is being put into growing the demand side of music, despite overflowing riches. There is wonderful, novel, era-defining music being made, but no support systems to surface it and to present audiences with events and experiences — big and small, magnificent to intimate to wacky to mysterious — that create wonder and communicate the majesty/fun of music even a few footsteps [from home].

For each fête de la musique or piano day in New York City, there could be hundred other days, a hundred thousand shows held in buildings just sitting around, a hundred million new listeners curious to check out which up-and-coming local acts are playing at the local park this week. That’s just one thread of possibility extrapolated along one known pathway, before anyone gets creative!

Growing the number of artists ad infinitum will be a fruitless endeavor if we cannot also grow the demand for those artists. Part of this growth should be focused on events. But another part of it should be focused on fostering a love for music in our schools rather than demoting it to an extracurricular.

#10 Absurdly Long Copyright Terms Incentivize Us to Invest in Music’s Past at the Expense of Its Present

Recently, Kendrick Lamar released the diss track Not Like Us. Lamar, the song’s sole credited songwriter, will control the copyright of that song until 70 years after his death. Really. Copyright goes beyond the grave. If we assume the Compton rapper lives to be 80-years-old, that means Not Like Us won’t enter the public domain until 2137.

Don’t get me wrong. I am an advocate for intellectual property protections. I just believe that those protections should be for a much shorter period of time. These absurdly long protection periods create a strong incentive for labels to prioritize the hits of yesteryear over developing new talent. Developing talent is risky. Repacking The Beatles’ catalog for the umpteenth time isn’t. But you don’t get a band like The Beatles unless someone somewhere takes a risk on a nameless artist.

#11 Songwriters Don’t Get Paid for the Performance of Their Songs in Movies

As we’ve established multiple times throughout this piece, the regulations around how songwriters get paid follow little logic. One unfortunate quirk of this logic — or lack thereof — is that songwriters don’t get paid when a movie is shown featuring one of their songs. Here’s what Donald Passman writes about this in his handy book All You Need to Know About the Music Business:

Due to some fancy footwork by the film industry a number of years ago, PROs are not allowed to collect public performance monies for motion pictures shown in theaters in the United States. There is no logical reason for this (showing movies is certainly a public performance); it’s just historical and political.

If you’re a little confused, let me illustrate this with an example. Elton John’s song “Tiny Dancer” was famously featured in the Cameron Crowe film Almost Famous. Crowe had to get permission from Elton John and Bernie Taupin, the writers of the song, to use it in the film. Furthermore, he almost certainly had to pay them for the right to use the song. That said, John and Taupin do not receive any monies each time Almost Famous is screened in the United States. Based on the fact that songwriters receive payment in this situation outside of the United States, we know that a hit film can generate hundreds of thousands of dollars in performance royalties for a songwriter.

#12 Hearing Issues Might Soon Plague the General Population

Despite the fact that musicians experience hearing-related issues at a much greater rate than the general population, I don’t think musicians protect their ears enough. Still, most musicians are at least aware of the fact that continued, unprotected exposure to loud noise will lead to hearing loss or tinnitus. I don’t think the general population is aware of that, though.

According to a 2019 report from the World Health Organization, “Nearly 50% of people aged 12-35 years — or 1.1 billion young people — are at risk of hearing loss due to prolonged and excessive exposure to loud sounds, including music they listen to through personal audio devices.” If you listen to music via earbuds, I strongly recommend getting a pair with noise cancellation technology. This allows you to enjoy music without having to blast it to overcome your surrounding environment.

#13 Major Label Layoffs Are Centered on People Necessary for Artists to Succeed

“In the past twelve months alone,” Billboard wrote in March 2024, “Warner Music Group, Atlantic Music Group, SiriusXM, Amazon Music, TikTok Music, CAA, Discord, BMG, TIDAL and Spotify have all cut staff.” Given how quickly these companies expanded over the last few years, the layoffs are not a shock. Nevertheless, those layoffs, especially at the major labels, have created great difficulties for developing artists. Many of the people laid off were those responsible for shepherding and marketing up-and-coming talent. With less staff, developing artists are the ones most likely to receive less attention and advocacy.

#14 There is Very Little Regulatory Oversight in Recorded Music

I started off this piece noting how the US federal government is trying to break up Ticketmaster. Even before the announcement of this lawsuit, the live music space received a ton of criticism for its anticompetitive practices. At the same time, the recorded music space receives almost no press despite being just as anticompetitive.

There are three companies that control nearly every piece of popular music that you hear: Universal Music Group, Warner Music Group, and Sony Music Entertainment. Anytime a new style of music becomes popular, these labels will just buy smaller labels that have artists making that music. We saw this when Sony bought independent label AWAL as independent artists began to account for a larger percentage of plays on streaming services. We also saw this when Universal acquired African label Mavin as afrobeats have exploded globally.

Almost none of these purchases receive regulatory scrutiny. That’s a problem. When three companies control most popular music, they cannot only limit the ability of artists to negotiate but they can prevent streaming services and other musical technology companies from innovating.

US-based Chris Dalla Riva is a musician who spends his days working at Audiomack, a popular music streaming service. He writes a weekly newsletter about popular music and data called Can't Get Much Higher. His writing and research has also been featured by The Economist, NPR, and Business Insider.