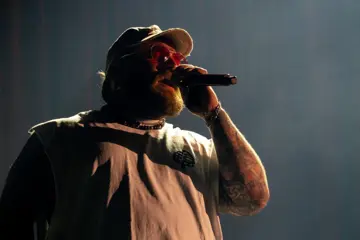

SG Lewis

SG LewisHeader image and in-article images by Harvey Pearson.

“Oh fwoor, what?! I haven’t even heard the final version in a club yet!”

SG Lewis is on the other side of our Zoom call, beaming with a brightness that could almost light up the club I just told him about, the one whose speakers blared out Impact - his single with Robyn and Channel Tres - a few weeks before we talked.

Impact, like much of SG Lewis’ debut album times (out now via PMR / Caroline Australia), was made in a time where the club music it’s influenced by was silenced; the majority of dance music havens closed with restrictions preventing the spread of coronavirus. Despite the surrounding environment it’s released in, times is indebted to club culture, from its themes of freedom and escapism to disco-tinged euphoria it aims to capture and emphasise.

To hear that glimpses of it are being played in parts of Australia - in places where community transmission of coronavirus has been non-existent and dancefloors are allowed to thrive - is enough for SG Lewis to consider moving almost 15,000 kilometres away, and undertaking the mandatory quarantine period the Australian government has imposed on international travellers. “I need to get down there. Who cares about the two-week quarantine or whatever, let’s just get down there and let’s go.”

SG Lewis - born Samuel Lewis in Reading, England - has always been indebted to dance music. The festival his hometown is renowned for - Reading Festival - was an early adopter of electronica in the UK festival space, and seeing Crystal Castles at the festival in 2009 proved a light-sparking moment for Sam as a bright-eyed 15-year-old. However, the real adoration of dance music came three years later, seeing Ben Klock play at Liverpool club event series Chibuku (a place where SG would later have a residency of his own).

“I remember walking into this dark place with black-painted walls and strobes flashing, with Ben Klock playing techno through Funktion One speakers. I remember just feeling it in my chest.” Reading Festival guests like Crystal Castles may have welcomed SG Lewis’ earliest experiences with dance music, but the Ben Klock show was his first foray into club culture, something he couldn’t really experience in Reading’s then-nightlife options of pubs and Top 40-esque clubs. “It felt like discovering something that I knew was going to be really important for the rest of my life,” he reminisces. “I was excited, curious and intimidated all at once.”

It’s a thrill that SG Lewis has been seeking - and finding - ever since; the rush of feeling relentless bass against the core of your chest mixed with the euphoric freedom that comes with the dancefloor, and the mixing of people from all backdrops - of all walks of life - with a shared interest in letting themselves go, and dancing their troubles away. He’d eventually start DJing himself in an attempt to bring those glimpses of freedom to others, expanding his tastes to niches of dance music founded on the principle of freedom and escapism: funk, disco, house, techno.

Like many DJs, the artistry of dance music led him to produce dance music of his own, with the SG Lewis moniker - modelled after his own name, Samuel George Lewis - making its debut in 2015. Initially, SG Lewis’ imprint on dance music came from hip-hop-inspired electronica inspired by notorious beat-makers like The Neptunes; his sample-ridden tunes fitting perfectly into the Majestic Casual and Soulection aesthetics of the mid-2010s electronica scene. Slowly, however, his work began to take more qualities from disco and house music, welcoming collaborative guest features and sharp instrumentation that fused his funk productions with pop mannerisms that would make SG Lewis one of the break-out acts of the ‘Soundcloud era’, and one of the period’s few acts to establish a larger audience in the days since Soundcloud’s demise.

Throughout 2018 and 2019, SG Lewis attempted to recreate the thrill of the club culture he’d become so fascinated with through the means of a soundtrack of-kinds, depicting the hazy night outs that ignited his passion for dance music. In a series of three EPs, he captured ventures through club culture in chronological order: Dusk, depicting the boozy warm-up; Dark and its representation of the club at its most anthemic and lively; and finally, Dawn, the hazy and low-key morning after. As a packaged release, they capture the heights of a night out and the rushing emotions that can come alongside, opening the doors for Lewis as a go-to producer for other musicians attempting to recreate a similar, disco ball-lit feel: Dua Lipa (Hallucinate), Victoria Monet and Khalid (Experience), and Aluna (Warrior) included.

Disco music has a dark history. It was innovated and popularised by Black, Latino and queer Americans in the late-60s, seeking refuge from the darkness of the socio-political atmosphere surrounding them. It was a place for minorities to dance; a home for those refused entry - if not attacked and beaten at entry - of more contemporary nightlife, which at the time, was catered to solely white, heterosexual audiences. It was a place for these marginalised communities to not just be themselves but to celebrate themselves in crowds and on stages, in a time where the world was stacked up against them.

Disco music was founded on the principles of self-expression and community, something which for the most part stayed as its popularity spread both throughout the US and internationally. By the end of the 1970s, disco was synonymous with the strength it gave the Black, Latino and queer communities, so much so that people angered by this attempted to tear it down: trashing nightclubs, launching radio smear campaigns, even infamously burning disco records at a baseball game. The genre’s popularity since then has revived itself a few times, albeit often at the hands of those who seem not to understand its history, and the power it once brought to those affected by bigoty.

“I think that it’s really important to go back and understand the history of the music you’re inspired by, and understand its roots and how it’s changed over the years,” Sam explains, and that’s exactly what he did. He researched the history of dance music and its role in the greater socio-political environment, flicking through old disco records while highlighting a book by Tim Lawrence - Love Saves The Day - as a particular must-read for producers working in the dance music space. “It made me have a great appreciation of where [disco music] came from, and how it’s queer, Black music that was born from the warrant of places to celebrate yourself and your community.”

“I think knowing and appreciating that made sure that I wasn’t just making the music, but knowing its history and where it came from. More than that, I wanted to dive deeper into it so I could lead anyone listening to my music down the same history, so they’re more knowledgeable too.”

times is an exploration of disco’s early history, with an ethos of reimagining the escapism dancefloors brought during the early-1970s, brought forward into the present time. It doesn’t attempt to reinvent the disco wheel or claim it as SG’s own (something “incredibly important” to Sam), but instead builds upon its foundations and earliest beginnings, modernising the euphoria captured within and placing it within a current-day context. It’s timely too, providing club-lit escapism to those needing it in a world where venues have been quietened to a hush; in a world where venturing to the club havens that these communities still rely on is a legitimately deadly and irresponsible move.

Across times, SG Lewis is able to whisk you away and encourage cathartic, disco ball-lit release - even if only for 40 minutes. The Rhye-assisted opener Time beckons the same smile-widening charm as Music Sounds Better With You, as Feed The Fire - featuring recent break-out Lucky Daye - adds a soulful twist to SG’s disco pace in a similar way pioneered by disco darlings like Donna Summer, strings and all. Even the album’s less strictly-disco moments - like Heartbreak On The Dancefloor or the Lastlings-featuring All We Have - move with a subtle euphoria, encouraging you to seek the solace of the dancefloor, and the intermingling, like-minded communities you can find within.

In saying that, the album has a few key moments that tap into disco’s escapist qualities at their most potent. Back To Earth is one that has Sam in the centre spotlight, with his auto-tuned vocals dancing amongst one of the decade’s best bass guitar riffs. The other moments enlist some of dancefloor euphoria’s pioneering artists in Nile Rodgers and Robyn; two musicians that understand the strengths of club culture catharticism better than anyone else on the planet. Rodgers’ guitar is instantly recognisable on One More - a song about dancefloor relationships written pre-lockdown - while Robyn’s energy on Impact is therapeutic through-and-through, channelling the same energy she carved on sound-defining records from her past.

“Sam made this instant thing, it’s a special skill to make a song that hits you right away the way Impact does,” Robyn says on creating the single with SG Lewis and Channel Tres. “The track just gave me the feels and it wasn’t hard to write a chorus to it, especially with Channel’s vocals on there already. Channel Tres came on tour with us last year so I know how strong he is on stage and hopefully sometime in the future we will get to be on stage together, with Sam, performing this song.”

Talking about the album with Sam, it’s clear that amongst the key points of times is to celebrate the foundations of disco music without removing its context, and removing its importance in Black and queer history. It’s a lesson in the history of dance music as much as it is a lesson in pop songwriting or funk production - both of which times excel in - and the meticulous research that’s gone into the album’s creation shines with its authenticity, in how it sounds and in how SG explains its meaning.

Throughout the album and its roll-out, times has played close attention to honouring its influences, much more so than any other disco-influenced record released by someone of SG’s stature. When it came to creating video content for Impact, for example, he enlisted non-binary RuPaul’s Drag Race alumni Shea Couleé and Detox for a video performing the track, and Nile Rodgers’ imprint on the record goes beyond his one credited guest feature; the visionary helping SG build the blueprint for the record as they collaborated.

“The impact of [Nile Rodgers] on times couldn’t be understated, because he’s really built the whole foundation of my career,” Sam beams. “To have him be a part of the record, guide me through it, and give his tick of approval is so important and so humbling.” The same goes for Robyn too, obviously: “I mean it’s Robyn, there’s a reason why people care about her music as much as they do,” he laughs.

In the end, however, times is a record that stands tall as SG Lewis’ own, and one that comes with many learnings for someone only just beginning to tap into a newfound passion for dance music’s history. “I think I just realised how indebted I am to dance music and club culture,” he says, asked what he took away from creating times. “Some people look at dance music as this aesthetic thing people do on the weekends, but a lot of my most treasured memories are with people I love at festivals and clubs listening to dance music, and I learnt not to take that for granted – especially with everything at the moment.

“I just hope that this album can soundtrack some of those future memories to be made, and that people make the most of it.”

SG Lewis' debut album times is out now via PMR / Caroline Australia.

Follow SG Lewis: FACEBOOK