It’s not news that live music venue shut-downs cause pain at the time they are announced. But what happens years, or even a decade and a half after they’re gone?

On Gadigal land in Surry Hills, The Hopetoun Hotel was famously once the venue that Paul Kelly couldn’t get a gig at. Its official capacity was 189 people according to a sign on the door, but it would regularly hold double that. From the early ‘80s until its sudden close in 2009, the pub featured the who’s who, who’s that and who that could become of music. It was also mostly free or low cost to attend, meaning artists and audiences could get in and learn their place in the scene without having to worry about being flush enough to belong.

Today The Hopetoun (aka ‘Hoey’) still stands in the same spot. It’s not quite derelict, but certainly very closed. It’s been 15 years this September, and its slow decay stands as both a sad reminder of what was to those that remember, and a curiosity for those Gen Ys and Xs who now live in the very expensive surrounding real estate wondering what the fuss is about.

What hope is there in the (still-closed) Hopetoun?

We’ve been working on a project about The Hoey for over a year now. It started as a little idea using resources housed in the Powerhouse Museum in Sydney – a few floor plans and some other pub paraphernalia. It slowly grew as we introduced interviews – we thought maybe ten people would agree, but we’re now closer to 100 participants. The City of Sydney has provided a grant to help as well.

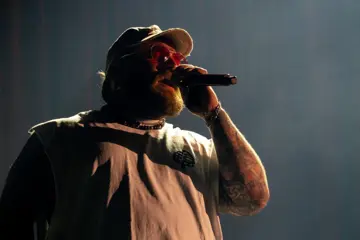

Many of the artist interviewees are now icons of the local scene – Tex Perkins, Tim Rogers, Sarah Blasko and the like; we’ve even been able to also interview icons of the industry proper, like Millie Millgate, now head of Music Australia, who started as a booker at the venue back in the day.

Artists, promoters, journos, publicists, publicans and punters – they’ve all been brimming with memories. There’s been melancholy remembering lost friends, figures and financial opportunity for sure, but also an undercurrent of hope.

While we’re talking about a venue lost, for the most part the people come from a place of optimism. Optimism for what was, but also for the impact it continues to have and perhaps could have again.

Optimism is what has always made the Australian music ecology work. We’ve never been flooded with cash and resources (especially not now). And that’s not stopped us in the past – which is where optimism comes from. If we’ve done it before, surely we can again. Just what was the formula again?

For The Hoey, the lack of money manifested in Rock Against Work shows – mid-afternoon, mid-week gigs with epic headliners. Some say Rock Against Work was held on dole day so that benefit cheques could be traded at the bar (an unverified but glorious rumour). Others say the Rock Against Work shows were designed to make the most of otherwise unused time – time when the neighbours would likely be at their nine-to-fives and wouldn’t notice the noise.

Low-cost-but-high-return initiatives The Hoey bookers and punters also supported were new acts – knowing that those learning their craft may have a crowd of family and friends as well wishers who will drink until the music sounds better. Of course, it was a delicate dance, and the skill was to mix the truly green with the truly talented, ensuring that artists and audiences got a full range of experience.

Another vital piece of the puzzle was local media support. During The Hoey’s heyday it was street press and newspapers of all types, which then expanded to early online gig guides, blogs, vlogs and message boards. Genuine word of mouth was also key. Of course, these were supported by other businesses – ad spend from not just record companies but all sorts of businesses; has this changed today? And if so, at what cost not just to the musicians, but the community?

What’s been most telling (and hopefully) optimistic about researching an old venue is rediscovering how diverse the lineups and events at The Hoey really were. Despite some of the histories suggesting bloke rock and not much else, deep diving into The Hopetoun’s history has shown a different reality.

Over the years The Hopetoun stage was shared by a wide range of artists across ages, genders and genres – somehow, the record has forgotten these. While our research is about retelling and reminding, it’s worth considering why the ‘boys who rock’ story dominates. Was this one angle offered at expense of other stories, or just a tap not yet pumped by an interested party?

This is where going back to documents like The Music’s predecessors Drum Media and On The Street has helped, as well as other community archivists like an incredible punter/photographer Bryan Cook. While superstar Aussie rock snapper Tony Mott also cut his teeth in and around The Hoey with big names and followed them as they soared, Bryan remained at the bar snapping away the keeper-ons.

Your local library might hold these histories – the State Library of NSW has just acquired an amazing update to their holdings reaching all the way back to the original 1980 launch of On The Street. But don’t forget too, The Music’s recent online release – the Hoey’s 2009 demise is there at least, as is lots of its ascension.

Sure, not everyone who was on The Hopetoun stage went on to make the big time. But it does seem like just about everyone who was in the audience went on to continue to love Australian music – for a big time.