John Farnham

John FarnhamJohn Farnham luckily avoided recording what became one of the worst songs in rock history while working on his mega-selling comeback album Whispering Jack. Not a noted songwriter himself, Farnham needed outside help to find tunes for the album and that job fell largely to his manager Glenn Wheatley, who had to work hard to get people to hand over their tunes. Farnham wasn’t a big name in the mid-1980s so there were a lot of famous singers in line ahead of him, and songwriters want their tunes to go to famous singers because there’s more of a chance of earning big royalties.

Still, Wheatley did what he could, and it seems he did quite a lot. He ended up bringing back boxes and boxes of demos: at least 3000 songs in all. ‘I listened to every one of them right the way through,’ Farnham said. ‘After a few you do get a bit brain dead, but you can’t afford to miss any.’

One of the songs hidden away in those boxes was the justifiably maligned We Built This City with its odd lines such as ‘Marconi plays the mamba’. Luckily for Farnham, he passed on that tune. He was lucky because US band Starship was on the verge of releasing it as a single, and while it went to No. 1 in Australia, the United States and several other countries the song went on to acquire a certain infamy. Oddly enough it was co-written by Elton John’s lyricist Bernie Taupin, though he insists his version was much darker and blamed an Austrian record producer for changing the song.

‘I still don’t like that song,’ Farnham later explained. ‘I just couldn’t hear myself singing it; it just didn’t appeal to me.’ This was fortunate for him: in 2011 a Rolling Stone readers’ poll voted it the worst song of the 1980s. ‘This could be the biggest blow-out victory in the history of the Rolling Stone readers’ poll,’ the magazine reported. ‘You really, really hate We Built This City by Starship. It crushed the competition.’

The song also finished in the top spot-on Blender magazine’s 50 most awesomely bad songs ever. ‘Over the years, as ’80s music began to sound dated and ludicrous – and no song sounds more ’80s than We Built This City – it developed a hideous reputation: the worst song of all time,’ GQ wrote in an oral history of the song.

Quality notwithstanding, it wasn’t the only song Farnham passed on that ended up being a hit for someone else. He also said ‘No’ to From A Distance, which Bette Midler later took to No. 2 on the US Billboard charts. ‘From A Distance had quite a pleasant melody,’ Farnham explained, ‘but I’m not overly religious and the song says “God is watching us”. Frankly, I would have felt uncomfortable singing that, because it’s not where I’m from.’

It was worth putting the effort into finding just the right songs, because there was a lot riding on the album that became Whispering Jack. Farnham’s career was in a lull – he was viewed by many as a has-been from the 1970s – and he was flat broke. After recording the album, he didn’t even have enough money in his pocket to take his son to McDonald’s for his birthday.

It had been quite a fall from the heady days of his early career. Born in England, his family came to Australia via the assisted migrant scheme, which made him a 10-pound Pom. The family settled in Victoria, Farnham finished school and began a plumbing apprenticeship but he was also singing in bands, which is how his first manager Darryl Sambell found him. Farnham signed with Sambell, who marketed him as Johnny Farnham. The first big move was getting him to record Sadie, The Cleaning Lady. Both of them recognised it as a cheesy novelty tune, but it landed him a No. 1 single straight out of the gates. Later it was an albatross around his neck as he tried to revive his career.

Through the 1970s Johnny Farnham released a number of top-10 hits, was named King of Moomba in 1972 back when such a thing was a big deal and TV Week readers voted him King of Pop five years in a row. He also dabbled in stage musicals, meeting future wife Jillian in one where she was hired as a dancer. As the 1970s came to a close Farnham found he was in a lot of trouble. He was hit with a big bill for unpaid taxes for the previous nine years and a restaurant venture failed. It was a combination of events that sent him broke but also led to him coming under the wing of Wheatley, a manager who showed extraordinary faith in Farnham.

The pair had known each other since the late 1960s, when they became flatmates. Farnham went above and beyond standard flatmate duties for Wheatley’s 21st in 1969. Wheatley’s mum had sent him a bottle of champagne as a gift, which he absentmindedly left in his car for too long, and there it sat for hours with the hot sun doing its worst. When Wheatley finally popped the cork and drank the contents, he found himself head in the toilet bowl throwing up for quite a few hours. Farnham regularly went in to check on him. ‘I saved his life, you know,’ Farnham later said. ‘I rescued him from drowning in the toilet bowl. We became good mates.’

It could be suggested that Wheatley owed him. Farnham decided to let Wheatley manage him in 1980 and gave notice he was now John Farnham; the boy Johnny Farnham was gone. The attempt to move him away from the teen-star image to one as an adult entertainer started with a cover of The Beatles’s ‘Help’. Given his dire financial circumstances, it was somewhat autobiographical: Farnham’s power ballad version reminded people he had a good set of pipes and they sent it into the top 10.

In 1982 Farnham replaced Glenn Shorrock as lead singer of another Wheatley-managed act, Little River Band. For the cash-strapped singer it must have seemed like a way out into the light. LRB had made it big in the US so surely the money would soon flow, but it wasn’t to be the case. By the time Farnham joined, LRB were on a downward trajectory. There were personality clashes that had been well hidden and the band’s finances were suffering because of huge recording advances they had received. With album sales not strong enough for the label to recoup those advances, LRB was in debt.

Not even songwriting royalties, which can’t be touched by labels, were a gold mine. Farnham penned the catchy Playing To Win but suffered because of the insane way the band calculated royalties. ‘The most anal thing that I observed was when they got down to the end of the project,’ assistant producer on the Playing To Win sessions, Rand Bishop, said. ‘They listened to every song and negotiated writer’s shares down to the subpercentages: like one guy would get 9.14 per cent. They would divide every line of a lyric and every line of music and claim ownership.’ In the end Farnham got 55.5 per cent of his own song, easily the best on the album.

On stage there was friction between Farnham and long-time band members Beeb Birtles and Graeham Goble, who wanted to rein in the new guy. Sometimes that meant giving him just six feet of mic cable to stop him roaming the stage, while at other times his microphone stand was gaffer-taped to the floor. When the label dumped the band in 1986, Farnham took it as his cue to leave. He had found being part of a band where everyone got a say in decisions quite stifling: he wanted to be the one calling the shots. Also, it was impossible to ad-lib during a song when three other members were singing harmonies and expecting the tune to be the same night after night.

Farnham and Wheatley agreed it was time to record a solo album. While Farnham worked on the album Wheatley had the task of signing a record deal, which proved to be a hard ask. Record company after record company passed on Farnham, with that Sadie song in the backs of their minds. Even when Wheatley played the stuff Farnham was working on there were no bites.

Wheatley ended up at the bottom of his list: RCA Records. ‘In those days RCA Records was the absolute last resort when it came to record companies,’ Wheatley wrote in his autobiography. He played the boss a demo of a song called You’re The Voice but still had to throw in his own label, WBE, to sweeten the deal. RCA was keen to acquire a label with local acts such as Real Life and Moving Pictures because they had no Australian acts on their roster.

‘Here was a chance for them to change the image and perception of the company in one move,’ Wheatley wrote. Farnham signed with RCA, which was a slight relief for Wheatley: he had such faith in what Farnham was doing that he had been paying for the recording sessions. He had even remortgaged his house to pay what was up to that point a $150,000 bill. ‘That was a lot for an album in those days,’ Wheatley said. ‘We had people on the payroll, people employed to look for songs. It was expensive because it took a long time to make. We were getting over John’s pop star days.’

While the label had liked what it heard in You’re The Voice, the last track sourced for the album, Farnham almost hadn’t been able to get his hands on the song. Based in the UK, co-writer Chris Thompson was inspired to write the song after 100,000 people marched to Hyde Park to support the campaign for nuclear disarmament. ‘I’d overslept and didn’t make the march,’ Thompson told Cameron Adams from The Telegraph. ‘We were watching it on TV. I was annoyed at myself and that’s where the idea for You’re the Voice came from. If you want to do something you have to go out and do it yourself.’

Thompson’s label didn’t like it, figuring the era of protest songs was over. Farnham felt otherwise: he heard the song and instantly knew it was for him. However, Thompson wasn’t too keen on the idea. ‘I got a call from my publisher saying “This guy called John Farnham from Australia wants to record You’re the Voice,’ Thompson told Adams. ‘I said, “You’ve got to be joking! He’s not doing it’.” I’d grown up in New Zealand and all I knew about John Farnham was Sadie The Cleaning Lady. I told my publisher he’s like a joke in Australia and absolutely no way is he recording You’re the Voice and put the phone down.

‘Two hours later I got another call saying, “He really wants to do it, he’s making this big comeback record, he wants this for the album.” They persuaded me to allow him to record it — my feeling is he’d already recorded it — and if I didn’t like it, I could say “No.”’

It took three days for You’re The Voice to be mixed, a lot of time for just one song. It was likely in part due to things such as using the slamming door of a car to replicate the sound of the drums, and maybe the bagpipe solo that had been Farnham’s idea. When Wheatley heard it he was disappointed: it didn’t give him goosebumps like the demo version had. Farnham read the look on his manager’s face and said, ‘You don’t like it, do you?’

‘There’s something about the song that isn’t as good as the demo,’ Wheatley replied.

Farnham said, ‘It’s the vocal, isn’t it?’ then rolled up his sleeves and went back to the studio, demanding the lights be turned off and the volume turned up in his headphones. ‘He put the headphones on and put in a vocal performance as only John knows how,’ Wheatley wrote. ‘The experience that night was awesome. Driving home we put the rough mix of his new vocal on in the car and I knew we had a hit.’

Farnham still had his doubts. Keenly aware of how much was riding on the album, he went into a sort of depression after handing over a tape of the finished product to Wheatley with the note ‘This is the best I can do. Thanks for the chance. Love, John’. He spent the six weeks until the release holed up in bed at home, rarely surfacing. ‘After finishing the album, I didn’t feel like eating for two weeks,’ he said. ‘One time I was literally lying on the lounge room floor in the foetal position, sobbing with fear. It was just awful.’ He didn’t even want to go to the album’s listening party, sobbing in the car and worrying that no one would like it. His wife Jillian told him to get out of the car and go through with it.

Whispering Jack was released in October 1986, with You’re The Voice as the first single. Promotion was tricky at first, with some radio stations telling Wheatley ‘We don’t play Johnny Farnham.’ However, when one FM station broke ranks the others soon followed, sending the song to No. 1 for seven weeks. Despite being released late in the year it became the biggest-selling song of the year, and the album held the top spot for a massive 25 weeks.

Soon afterwards Wheatley was driving in his car with Farnham in the passenger seat. ‘You’ve got to appreciate this,’ he said to Farnham. ‘As we speak, we have the No. 1 album in the country. We have to enjoy this moment.’ Farnham didn’t say anything, and Wheatley looked over at his mate: tears were streaming down his face. With all the cards stacked against him, Farnham had come through.

In 2023 the song was gifted to the Yes campaign for The Voice referendum as the soundtrack to an ad. It looked at defining moments in Australian history, from the 1967 referendum to including First Nations people in the census, the Mabo decision, the America’s Cup and Cathy Freeman’s 2000 gold medal. Farnham said: ‘This song changed my life. I can only hope that now it might help, in some small way, to change the lives of our First Nations peoples for the better.’

Not everyone welcomed the song’s use, with some taking to social media to vent their outrage and post photos of their garbage bins full of Farnham CDs – which they presumably fished out not long after they took the photo.

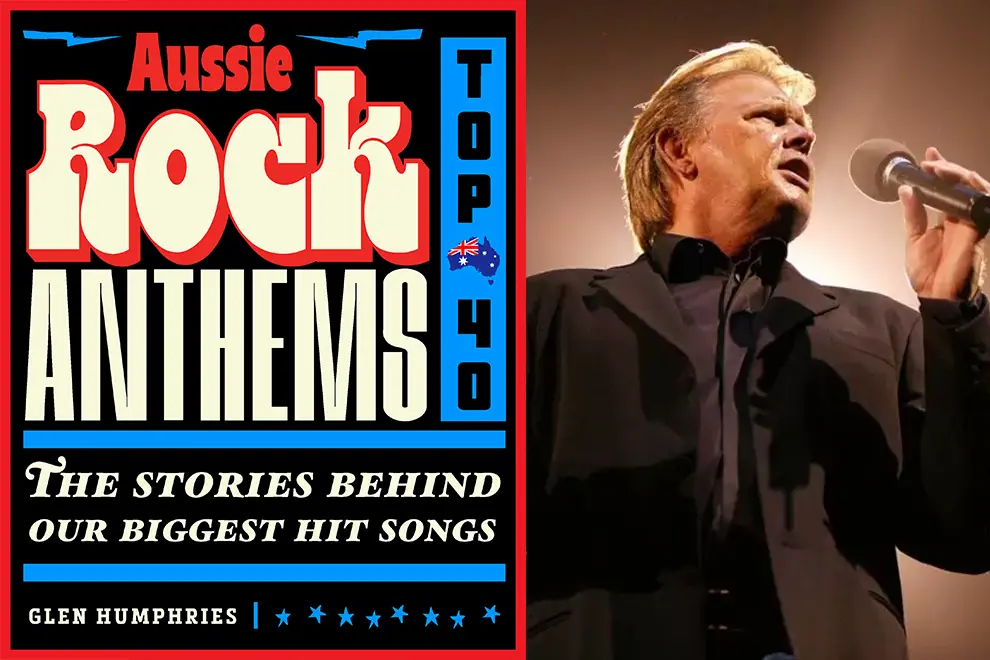

This is an edited extract from Aussie Rock Anthems by Glen Humphries (Gelding Street Press $39.99), available at all good bookstores. You can find out more about the book here.

Glen Humphries will be launching Aussie Rock Anthems (Gelding Street Press) in conversation with Jeff Apter at Ryans Hotel Thirroul (31 July at 6:30 pm). Entry is FREE; bookings are essential via Collins Thirroul. You can also catch him in conversation with Michaela Bolzan at the Southern Highlands Writers Festival on Saturday, 27 July.