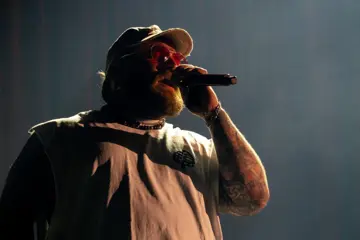

Underscores

UnderscoresThe internet and its culture have irreparably damaged the music industry in countless ways, but they’ve also allowed its creative corners to thrive like never before. With the entire recorded history of music available at your fingertips, for example, emerging artists can tap into a virtually infinite well of inspirations, curating sonic palettes that would’ve sent our ancestors into hypomanic shock.

From that well comes records like Wallsocket, the career-defining second album from bedroom beatmaker-come-hyperpop princess Underscores – a kaleidoscopic fever dream that owes as much of its dues to Bruce Springsteen as it does to Skrillex. The hourlong epic oscillates from the brooding grit of horror movie soundtracks to the sugary shine of bubblegum pop, along the way taking detours into whiskey-soaked Americana, coloured in with wallops of fuzz and distortion – all without once feeling aimless or unkempt.

From the moment April Harper Grey launched the Underscores project at age 11 (some 13 years ago), it’s been a vehicle for her to experiment with the polychromatic sounds and styles she’s obsessed with. Roused by Porter Robinson and the aforementioned Skrillex, she started off making crunchy glitch-hop and brostep, before her coming of age led her scope to broaden with 808-laced beats à la Drake, effects-soaked vocals and quippy lyrics in the vein of 100 gecs, and an indie-pop shimmer pulled from the book of Imogen Heap.

Grey’s debut album as Underscores, 2021’s Fishmonger, marked an insightful snapshot into the person she was and the music that moved her at the start of her twenties. For its follow-up, though, she didn’t just want to evolve on those soundscapes – she wanted to honour the past and present with equal reverence. She explains to The Music, “I kind of zoomed out to the music I was listening to when I was growing up, and the music I listen to now, [which is] like a mix of really energetic pop music and really emotional, beautiful guitar music. And the biggest thing that gets me excited about music [in the present] is that you can find a way to combine things that seem very disparate, and make something cohesive out of them.”

Guitars certainly played a big role on Fishmonger, from the snarly pop-punk vibes of 70% and Spoiled little brat to the moody alt-rock flair of Kinko’s field trip 2006 – but the instrument was mostly utilised to elevate, not dictate, the structure of a song. That wasn’t the case when Grey was building out Wallsocket – the bones of most tracks were laid down with an acoustic guitar, and even after she’d fleshed them all out in Ableton, she looked to banjos, lap steels and slide guitar for seasoning.

“When I was growing up,” she reasons, “I really liked the sounds of those folkier and rootsier instruments – they make me feel real cozy, you know? So when I was making Wallsocket, I was just kind of like, ‘Well, why wouldn’t I try to incorporate that stuff?’ They’re some of my favourite sounds in the world.”

In developing the musical palette of Wallsocket, Grey made “a concerted effort to take elements from folk and blues and country, and try to distort them in my own way”. It’s unsurprising, then, that one of her biggest influences for the album was Springsteen; Wallsocket is the Monster Ultra Rosa-pilled answer to Nebraska, the conceptual tour de force The Boss dropped in 1982. Largely experimental, it explores the stories of blue-collar bozos with lives fraught by chaotic bursts of turbulence, illuminated by transient flashes of hope. The characters are complex and morally ambiguous, reflecting a rawness in the human spirit rarely touched on in mainstream music.

Grey captured much of that same essence on Wallsocket, albeit from a more fantastical direction: it’s heavily inspired by the political ‘horseshoe theory’ – the notion that the far-left and far-right are closer to each other than they are to the centre – detached from its roots and applied to the individual experience of selfhood. She pondered in a statement shared upon the album’s announcement, “Where in our lives are we so one thing that we wrap back around and become its opposite? That theory is riddled throughout the album.”

To ground the album in a narrative, Grey took the concept of Nebraska and adapted it to an idyllic small town in rural Michigan – one, it should be noted, that doesn’t actually exist. Grey herself hails from the bustling concrete jungle of San Francisco, but has long been enamoured by the aesthetic and culture of the midwest US – so she “spent a lot of time on Google Maps, just kind of poking around on Street View”, piecing together elements of many different town to create her perfect midwest fantasy.

The fictional Wallsocket sits on the outskirts of Detroit, from whence the townsfolk migrated – “you imagine those people sort of white-flighting their way over to this little one-horse town,” Grey muses, “and building it up over years and years and years.” With the concept in place, she continues, her creative mind was able to wander freely: “It felt like an encapsulation of all the themes I wanted to look at – both in terms of [Wallsocket being] a satire of what it means to be upper-middle class in America, and a look into this microcosm of society; who are the people living there, and what experiences are they having?”

Wallsocket follows the perspectives of three main characters – S*nny (a transgender girl battling a rare, but ultimately harmless disease), Mara (a victim of lucid nightmares, and obsessed stalker of S*nny) and Sarah (the hedonistic daughter of a billionaire, or as its said on her theme-song-of-sorts, an “old money bitch”) – all of whom are allegories for the parts of Grey she endeavoured to reckon with through songwriting.

She says of her process: “The thing I’ve been realising, the more I write songs, is that I don’t consider myself a very emotional person. I think when people listen to the music and they hear all of this angst or rage, or these sort of hard-to-talk-about topics and things like that, it can kind of seem like [I am]. And I think that’s the purpose of music for me – to have a place where I can figure out what emotions I'm feeling, and try to amplify them in a way where I can, like, zoom in and sort of interrogate myself a little bit.”

Virtually every track on Wallsocket went through significant rewrites – sometimes the first take would sound literally nothing like the final one (take for example Old money bitch, which started off as a remix of I Write Sins Not Tragedies by Panic! At The Disco – with the original demos often being a lot more autobiographical. Grey notes that she would tend to “do most of the emotional work in the first draft” of a song, then “whittle it down to a place where I could devote it to a separate character”.

Grey’s aim was to create something of a “middleman between me and whoever’s listening”, as she explains: “There was a lot of effort that went into trying to make something that wasn’t irresponsible, or like, oversharing too much. I wanted it to feel like I was feeding [these narratives] through a vessel, and then people can gather their own sorts of conclusions and stuff from there.”

It’s fair that Grey would want to distance herself from some of the stories told on Wallsocket – she obviously didn’t rob a bank (as portrayed on the opening track Cops and robbers), and she’s been quick to clarify that Johnny johnny johnny, a song about a trans girl falling prey to an online predator, is not based on a scenario she’d personally experienced.

That’s not to say Wallsocket isn’t a deeply personal album for Grey. “I wrote pretty much all of this stuff when I was 21 or 22,” she says – a point in her life when she was realising “there were a lot of personal things I wish I could have wrestled with when I was like 18 and first leaving the house. And then I realised, the majority of my fanbase is probably around that age range, so I felt like I could kind of speak to them, in a sense; the messaging of [Wallsocket] could be what I wish I’d had five years earlier.”

To that end, one of the most prevalent themes embedded throughout Wallsocket is the bridge from girlhood to womanhood, specifically through the lens of a trans experience. Locals (girls like us), for example, defiantly flips transphobic rhetoric into an empowering battlecry – “Stop me if you’ve heard this one before / Girls like us are rotten to the core!” – while Northwest zombie girl (one of four bonus tracks on the new Director’s Cut edition of Wallsocket) speaks to the turbulent myriad of interpersonal changes that come with transitioning. And of course there’s Johnny johnny johnny, which should boil the blood of any doll who’s had the misfortune of dealing with a chaser.

The most significant trans anthem on Wallsocket, though, is the henhouse!-assisted Geez louise – a breathtaking saga that vaults from gnashing punk to swampy blues, before flowering into a heartfelt ballad that erupts with a crescendo as grandiose as it is cathartic. It packs a lot of talking points in its seven-minute runtime, from conservative fearmongering to the sad reality that trans people with unsupportive families are more likely to commit suicide (“.41 at the back of my head / I know without my mother I’d be dead in an instant”), but at its core, Geez louise is about the lasting impact of colonialism on trans identities in Filipino culture.

“If you go back and read all the stuff that Spanish colonisers were writing about pre-colonial Filipino society, you’ll see there was so much variance in gender identities,” Grey explains, noting that people who did not conform to their assigned sex were often viewed as shamans – but that was eradicated when the Spanish invaded the Philippines and the societal landscape became dominated by Catholicism. “And now all my relatives are Catholic,” she quips, her tone underlined with hints of frustration and defeat.

Reading up on the history, Grey was swamped with emotions; “I felt angry about it,” she says, “but I was also like, ‘Well, that was hundreds of years ago – there’s nothing I could’ve done then, and things are getting better now.’” Those thoughts led her to reflect on the peaks and valleys she’s traversed along her own journey as a trans woman, thinking about “people who have been really supportive and people who haven’t”, the ways trans people are represented in mainstream media, and the struggles we face that cisgender people could never properly comprehend – “a lot of really heavy topics”.

On the plus side, she says, “I think that’s why [Geez louise] was such a cathartic song to make, and why it was so fun to have it go in so many directions – because it was such a complex, kind of frenetic thought process.”

Wallsocket doesn’t mark the first time Grey has written about trans experiences – Girls and boys (from 2022’s boneyard aka fearmonger EP) is one of the best songs ever written about the way trans women are often fetishised by straight men – but it shows her embracing that part of her identity more boldly than she has in the past. “There are definitely a couple of songs on Wallsocket where to fully get it, you probably have to be trans,” she chuckles.

Grey wasn’t always this open with her songwriting. “For a while,” she admits, “I was very much against writing about [being trans] because I didn’t want to be, like, one of those ‘special snowflake’ that makes being trans their whole identity or whatever – I wanted to be ‘one of the good ones’. But I got to this point where I felt like there were things I needed to wrestle with – that I think are important to talk about. So as time goes on, I’m definitely becoming more comfortable exploring themes of transness and stuff in my music. I have a lot more of a healthy view on it these says; I don’t think it should be something you need to internalise to be taken seriously – I think that ‘one of the good ones’ mindset is a very dangerous mindset to have.”

Of course, Wallsocket was not intended to be read strictly as a ‘trans album’, and even songs like Geez louise can resonate deeply with cis listeners who wouldn’t even think to consider the trans angle. “That’s what’s so amazing about music,” Grey beams, “or I guess art in general – once it’s out there, it’s yours.

“I guess I’m still trying to figure out how I feel about doing interviews, and talking about the stories behind my songs – because people always have different interpretations of the songs are about, often based on their own identities and their own experiences, and I think that’s really cool; there’s so many different things that people can take away from the same piece of music. And it’s like, whether or not my intention was to talk about this particular thing, if that’s how you interpret the song, then that’s what the song is about.

“You know, sometimes I do want the message to be really hamfisted – but sometimes I want to make the specific words I use a little more vague, or kind of artsy and stuff like that, because I think that helps people form their own relationships with the songs, instead of being told explicitly what they’re about.”

The town of Wallsocket might be fictional, but the way the songs on its namesake album cut deep and resonate with you on a spiritual level? That shit couldn’t be more real.

‘Wallsocket (Director’s Cut)’ is out now everywhere via Mom+Pop